On my dad at 100

5th January 2015

Well helleur.

Happy New Year and that.

This is a short blog about my dad, who would have been 100 on Boxing Day.

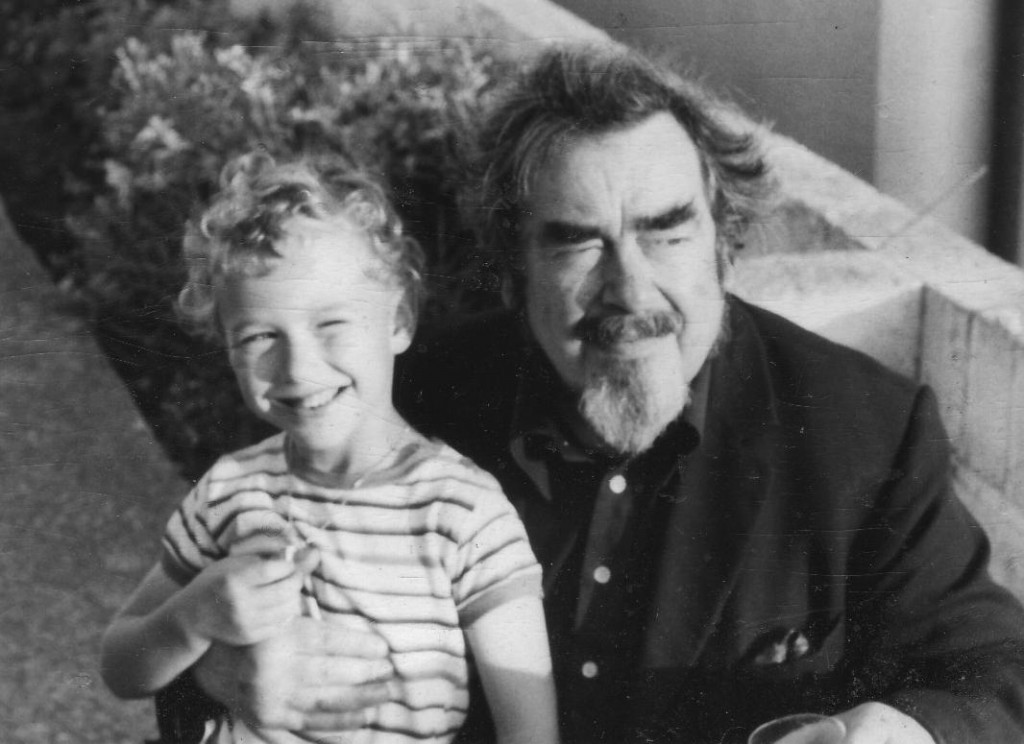

When I was born my father was 58. There are not many people who can say that, or remark casually that they have a half-sister who is 81 (or a half-brother of 72). Growing up I was constantly aware of his age. My party piece in the playground, rather shamefully, was to reveal how old he was to other children. “You’ve got it wrong,” they’d say. “Miss, Saul’s lying again!” When I was 11 my rugby master claimed he’d bumped into my grandfather on a train to Twickenham. “My grandfather, sir?” I said. “He’s not really a rugby man.” Half an hour later it dawned on me he meant my father. As a means of exaggerating his age Dad would always declare he was “in my 80th year” rather than admit to being a mere 79.

There are a number of reasons for my late appearance, the principal one being my mother, twenty years dad’s junior…

That he met her so late in life is due to my father’s messy life and late reinvention. He was born in Calcutta in 1914, got sent down from Oxford, blew an inheritance, married, went to war, divorced and found himself washed up on the shores of North Wales. For a time he lived with the wife of John Russell, Bertrand Russell’s son, before she developed schizophrenia. Eventually he found his way back to London and began reviewing books and reporting on sport for the Guardian and Observer.

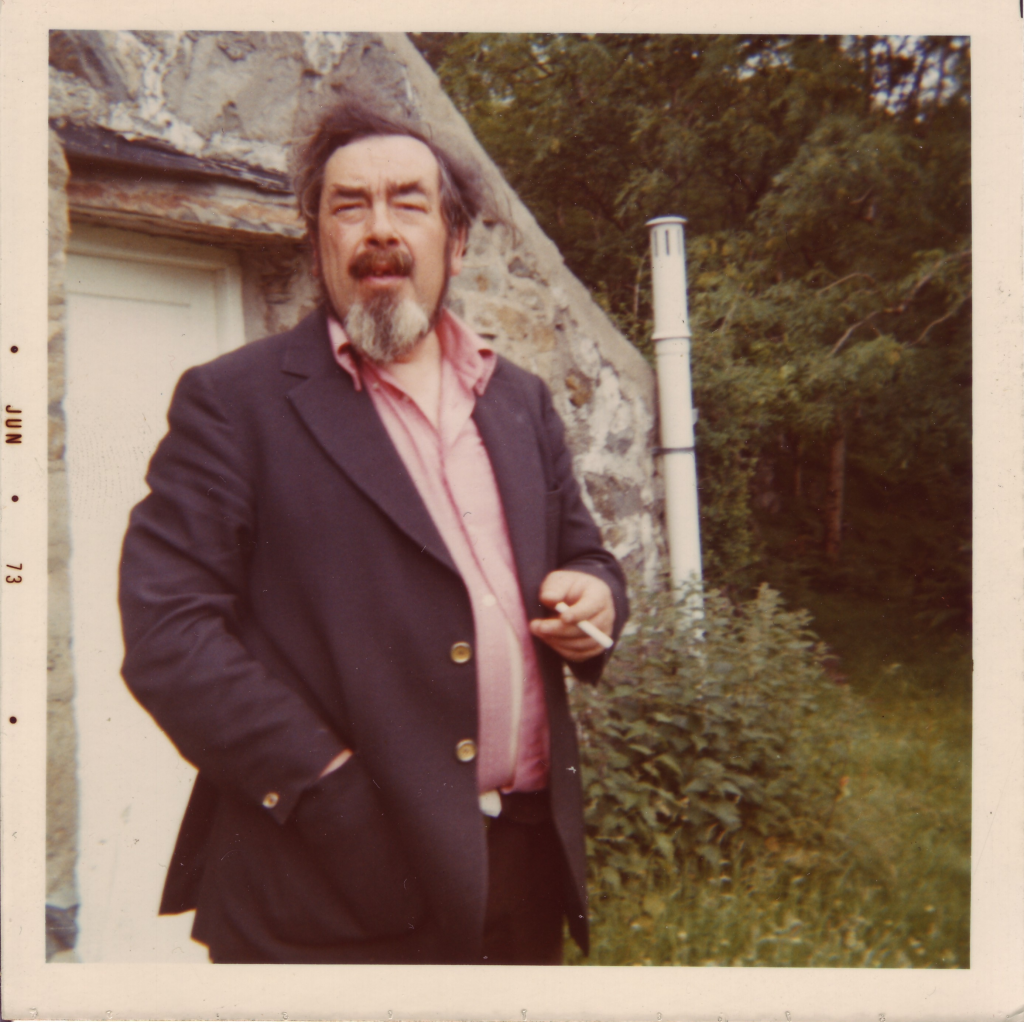

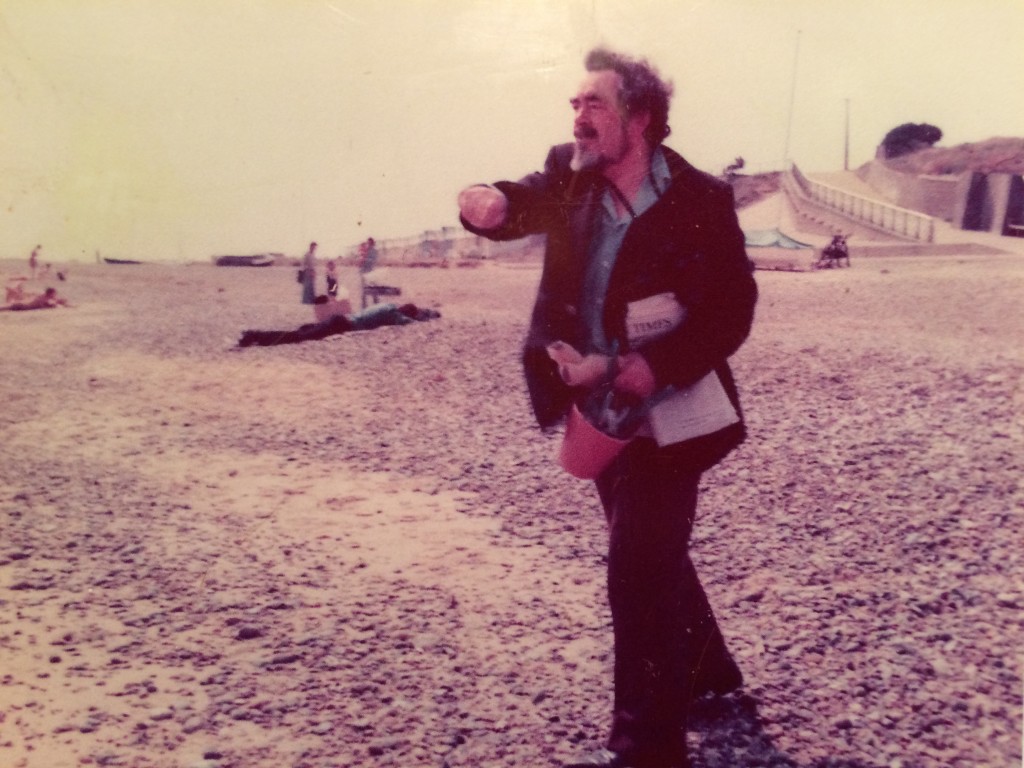

Despite his advancing years my father never behaved in an elderly manner. My grandfather, eight years his senior and half a mile down the road from us in Harpenden, seemed ancient by comparison. Dad had a full head of hair, a ready wit and a booming voice. Despite his age he was still able to throw a ball at me in the garden or take me to London for day trips. His body gave out on him briefly in 1982 when he suffered a heart attack but he lost some much-needed weight and bounded on for another 14 years – remarkable considering drinking, smoking and not walking anywhere were three of his favourite pastimes.

All those years in the wilderness had apparently preserved his energies. He would often stay up for two nights on the bounce writing his copy for The Observer. Of course by now he had to provide for a wife and young child. Four children preceded me, but it was only I he truly raised. This pained him (and later embarrassed me). It would certainly explain those dark moments alone in a chair. Sometimes I would ask what was the matter. He would allude to a misspent youth and some unfortunate choices, before, head in hands, lamenting, “the years that the locusts have eaten”.

I paint a mostly upbeat picture, but his age did affect me. I was terrified that he would suffer another heart attack while we were out, in particular when we travelled down to Lord’s. This was my biggest anxiety – this, and the ever-present threat that he’d say something embarrassing and loud to the crowd. My half-brother and I would do our best to keep him quiet, especially after a glass of wine at lunch.

Life was never dull with dad (except when he dozed off in the afternoons). He had a youthful outlook and was always excellent company. As I turned 18 he would often ask if he could accompany me to the pub (I never let him), or suggest we share an alcopop before bed (“for my thirst”). Looking back I can see he just wanted to spend time with me. My half-brother David recounts a tale of how they came to see me play cricket. I hit a six, dad high-fived my brother and shouted to me. When I didn’t hear he insisted they do it over and over again. I’m rather glad I didn’t see (especially with my brother nearly six foot, dad a mere 5’6”).

As I entered my twenties and dad his eighties there was an increasing poignancy to our meetings. Would this be our last dinner, our last Pimm’s, a final embrace? This became ever more true when in 1996 my parents moved to mid-Wales. Dad was now 81, my mother 61. I spent two weeks helping them settle in. At the end he seemed both surprised and upset that I was heading back to the South East. “Can’t you get a job up here in the forestry?” he implored.

Two years later I was sat at my desk when I received the call I’d been expecting all my life. Dad had died during one of his afternoon naps. He had gone on working until the last, squeezing out every last drop that life could offer.

When I think of him now I recall the liver spots on the backs of his hands, the thud of review copies hitting the floor as he dozed off in a chair, his huge physical strength, a ferocious temper, but also a great tenderness. A complex life made for a complex man but the years knocked the edges off him.

How to make sense of the past? It is now 16 years since his death. I was 25 when it happened. That’s a long time. I feel greater fondness for and understanding of him than ever, yet as the years slip by sometimes it’s as if he was never here, the proof of his physical being a strange, forgotten dream. Then I meet up with my half-brother David, we compare notes and he’s back in the room.

Mostly there remain his witticisms – it was he who coined the phrase ‘legend in his own lunchtime’ – along with endless anecdotes told and retold. One of my favourites is of my mum missing her pudding bowl and instead firing squirty cream across the dinner table. “Wish I could do that,” he deadpanned. My teenage self squirmed.

Not necessarily a fitting epitaph, but a quintessential one.

Love you dad.

*

*

*

*

You can find an essay I wrote about my dad here.

*

*

*

*