On promoting your book

29th July 2015

Books, eh? So many published, so few read. Trying to get noticed is the name of the game (I should know, I’ve played it. Let’s call it a draw to date).

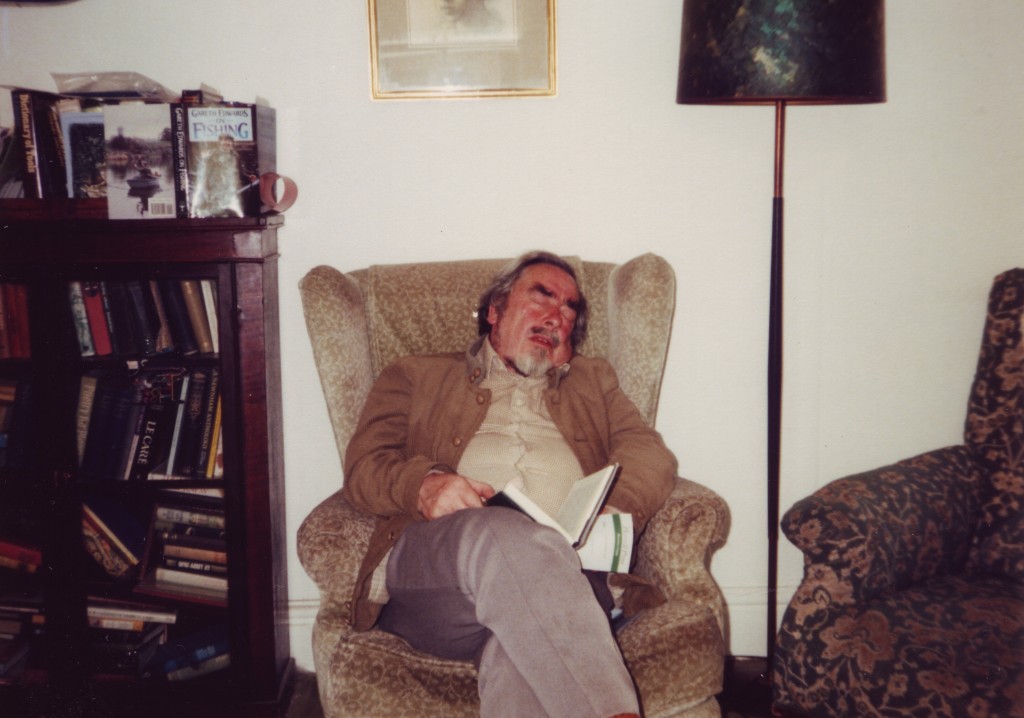

All will be explained shortly, but here’s a picture of my dad hard at work in our sitting room in 1986.

Late last year I had a novel published, which was nice. Very nice, in fact. Based on my experiences here are the three stages of publication:

1) Honestly, having a book published is more than I could have dreamt of. I’m so happy.

2) I just want people to enjoy it.

3) Why haven’t I won the Booker Prize?

Your book could be as good as Ulysses, War and Peace or Ant and Bee, but without the right push, momentum, luck, reviews or readers there’s every chance it will slip away unnoticed.

I worked closely with the publicity department of my publisher. I conducted numerous radio and local newspaper interviews. I had features published in The Independent (twice), The Jewish Chronicle and the Huffington Post, some of which focussed directly on my book, other more tangenitally. These are all means by which to draw attention to your writing. Plus I tweeted about it til I was blue in the finger.

And it’s worked – to an extent. People often ask how many copies the book has sold. I found out the other day and on balance I was pleasantly surprised. Most first time authors only sell a few hundred copies. I’ve sold a few thousand. The publishing house will have made its money back, and then some. The book’s doing OK.

Also: it’s still early. Books are like elderly aunts, they take time to catch on. The paperback’s only been out a couple of months. There are other radio and newspaper opportunities. The film remains a possibility.

There are a couple of features that I never placed and never will, however. In particular I wrote something about my father for the literary pages of the Guardian.

Those of you who know me and have followed this blog will observe that my father is – and forgive me – a leitmotif in my work. He remains an endless source of anecdote and material, an ongoing feast that I can tuck into whenever I choose.

The man at the Guardian said, “Would that I had the number of pages to put in everything that I like and is worthy…”

What I’ve really been working up to saying is that with nowhere else to place the piece…here it is.

***************************************************

My Father the Critic

Between 1965 and 1996 my father was a literary critic for the Guardian and the Observer. In this time he read thousands of books, submitted hundreds of reviews and bristled endlessly at the editing of his copy. He was a jobbing reviewer with the heart of a poet.

His was an unusual role in that he wasn’t himself an author, only a reviewer. This meant that when not at Lord’s or Twickenham moonlighting as a sports reporter he was sat at home reading. He did so seven days a week save for a brief respite around two every afternoon when his book would hit the floor, indicating a nap was underway. Proof copies would arrive at all hours of the day, books were piled knee-high throughout the house and grey parcel stuffing speckled the carpet.

His duties were straightforward. He was assigned a genre – often crime – to read, and would at the end of the month produce a run-down of the latest releases. This was interspersed with reviews of single books and general fiction. Other areas of expertise included boxing, cricket and fishing. If there were historical novels to cover he would do so under the nom-de-plume Stephen Vaughan so as not to queer his pitch.

Every couple of weeks he would disappear upstairs to write his copy. Despite years of experience these periods always resembled an adolescent essay crisis. Occasionally I would take him a cup of tea. The air always hung heavy with tobacco, the right hand side of his face tan with nicotine from the perpetual corkscrew of smoke that emanated from the cigarette that sat characteristically on his lips but remained forever uninhailed. His shirt was constantly stained and singed on the plateau where his hefty stomach would catch, invariably, a full three inches of ash. I would brush the ash from his belly and onto a floor thick with crumpled drafts, collect the empty cups and leave. He barely noticed me, as if in a trance. These 48-hour periods with little or no sleep culminated in bursts of two-finger typing.

Once complete he would hobble back downstairs in his dressing gown and call the copytakers. This comprised the somewhat archaic practice of ringing the Guardian (I doubt it was outsourced to India) and dictating his copy down the line. My father had his own phonetic alphabet: “A for Apple”, “N for Nuts”, “S for Sugar”, “V for Victor”. Often I would sit listening as he boomed his copy into the receiver. For years I thought those at the other end were called ‘coffee-takers’.

This method of relaying information was far from an exact science. Add to the mix a partially deaf man short on sleep and accidents were bound to happen. Thus “the county surveyor” appeared in the paper as “the Countess of Ayr”, whilst “the self-same arena” morphed amusingly into “the Selsey Marina”.

When feeling especially exhausted (or the literary editor especially generous) he would order a taxi to drive his copy all the way from our home in Harpenden to Fleet Street. I used to imagine it sat in the passenger seat, maybe buckled up, looking out of the window. One day the driver turned to my father and said, “Mr Wordsworth, have you heard of the fax machine?” From then on it was a short trip to the stationary shop.

My father fetched up on Fleet Street in the late 60s, in his early-50s. That he did so was the result of a much-acclaimed essay he wrote for a collection edited by the Observer’s principal reviewer, Philip Toynbee. This was a boom time for journalists, an era of long liquid lunches and hefty expense accounts. There were casualties, but as a homeworker – and a freelancer – he escaped the worst of the excesses. Every Wednesday though, under the literary stewardship of the Observer’s Terry Kilmartin, he would venture up to London to write what were known as ‘the headings’, invariably pun-based headlines for each review. Sometimes the meeting would take place at El Vino’s, the legendary Fleet Street watering hole. All too often sports editor Clifford Makins would accompany them, the man about whom my father coined the now well-worn phrase, “a legend in his own lunchtime”. On more than one occasion dad fell asleep on the train home and woke in Bedford, only to catch another back and find himself from whence he came.

The life of a reviewer is bound to be unsatisfactory. One has to be at least the equal of the writers one is reviewing, yet one rarely get the same credit and may even be viewed – incorrectly – as a parasite of literature. One is dependent upon a literary editor who may not have enjoyed your last piece, and may understandably have their head turned by a big-named author as reviewer. One has to read a lot, and a lot of drivel.

There were upsides: once a month he would lug a holdall of proof copies to Gaston’s bookshop on Chancery Lane and sell them for cash. An immensely strong man, more than once I accompanied him, dragging my own bag weighing in excess of 70 pounds. The acquisition of review copies could be fierce and he was particularly proud of winning a Mexican stand-off for a tome entitled The Butterflies of Royal Berkshire, netting him £30. Selling proofs was common practice. Those shy of a few bob would invariably grab a handful of review copies from the Observer office and cash in up the road. Kilmartin would arrange parties with the spoils, or distribute amongst his staff. It was also whilst working at the Observer that my father met and married my mother, a fellow reviewer.

Although he was a regular for both papers he was never on the books. This freelance status made him anxious, uncertain, quick to perceive sleights. I was in the room when dad had a telephone conversation with former Observer editor Donald Trelford, who informed him – quite justifiably – that he wasn’t in line for a pension. That he hoped otherwise was an indication of his naivety in matters of money. It also explains why he continued reviewing until his death at the age of 83.

My father’s legacy doesn’t stretch far beyond those who knew him. There are a smattering of his reviews online and a tiny handful of quotes on the backs of paperbacks, though these have virtually died out. But he was a lyrical cog in a magical wheel that was Fleet Street in the 70s and 80s.

‘Alan Stoob: Nazi Hunter’ by Saul Wordsworth (£8.99) is published by Hodder & Stoughton. Follow Alan Stoob on Twitter @nazihunteralan.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*