On riding a stage of the Tour de France

26th July 2013

(or how I overcame great adversity to fulfil my personal destiny)

Wotcha. How are the pigs? You keep pigs, right? Sorry, I must be mistaken.

For my **th birthday last December Joan bought me a gift to treasure: entry into the famously gruelling Etape du Tour cycling race. I rode it two weeks ago. This is my story.

(posey I know but it’s done now)

In the last 18 months my interest in cycling – watching, participating and to the detriment of my friendships, discussing – has been on the rise. I have sought out like-minded souls to ride with and similar sorts with which to discuss the intricacies of road racing. There is little question cycling is a ‘bug’ you can ‘catch’ and I’ve come down with it on a grand scale, spending days on end hovering over a metaphorical bowl chunking my guts up (analogy over).

I’m not alone. Recently I was chatting with Phillip, owner of my local bike shop.

“Phillip,” I said, “I fear my interest in cycling is increasing by the month.”

“That’s nothing,” he replied. “Mine does so by the hour.”

Phillip is currently scaling back his time in the shop in order to spend more time with his bike.

On the occasion of my birthday Joan handed me my special gift. This year the Etape route was to be stage 20 of the Tour de France. She’d also persuaded my cousin Luke to enter the race. Sunday 7th of July was duly written into my filofax (I have a filofax) and I began training.

In the early part of the year I undertook a handful of lengthy rides visiting friends across the country. Such occasions are great for getting fit as well as getting drunk. But what I really enjoy is the adventure. Riding 70+ miles along unfamiliar roads whatever the weather is a liberating experience. A (very) simple man on a simple machine challenging the elements, plus the odd stray dog/Yorkshireman. Unlike others I was never one to venture much beyond these shores in my earlier years. It’s as if my wanderlust is finally leaking out through the medium of elongated bicycle rides into Britain’s unknown.

I also planned to race. I’m a competitive person and I like to be challenged both physically and nasally. This manifested itself a year ago when I entered a race in Essex. I truly had no idea what I was letting myself in for and was totally unprepared for the speed. After twenty seconds I looked behind to see where I was in the pack, only to be greeted by the sight of my own shadow. I quit after two laps. My eyes were now wide-open.

My plan to race tied in nicely with riding the Etape du Tour. The extra level of fitness I would gain from racing could only aid me in my French odyssey.

I began racing in May at a closed-circuit track in Hillingdon, West London. I did OK. I was able to stay with the group. I found it exhilarating. It’s fast (you average about 25mph during an hour-long race). It’s also exhausting. In my last race I didn’t hear the bell – so tired I couldn’t even HEAR.

Meanwhile Luke and I trained together. We undertook what is known as the Coast to Coast, or the Way of the Roses: traversing the breadth of England from Morecame (Lancs) to Bridlington (Yorks). Another great adventure. This shot from my hotel bedroom in Morecame gives a flavour of what awaited us on the first morning.

Fast forward a day and a half of wind, rain and a great little pub outside York that laundered our kit overnight, and we were in Bridlington…

The weekend before the Etape we rode a hilly sportive in West Sussex. I say hilly; it was as nothing compared to what awaited us across the water but then it’s impossible to find like-for-like in England. The French have mountains. We have hillocks.

We rode it fast and well, packed our bikes into bike bags, drove them to Orpington for shipping then had a week before the event.

And then I became ill. Thunderously ill. In the early hours of Tuesday I visited bathroom 18 times in a two hour period. Gastric flu of some kind. I felt wretched. I couldn’t work or move, just sleep and stay close to the toilet. Sorry but it’s true. I won’t apologise again.

I met Luke at Stansted on the Friday morning. I felt rotten. My body hadn’t held onto anything for days. My pallid, expansive forehead was topped off with a film of sweat. I took an Imodium and two Nurofen before the flight. It seemed unlikely I’d ride. At least I wouldn’t have to re-assemble my bike.

On Saturday I felt a little better.

We had to register for the event in nearby Annecy. Our hotel was four miles outside the town. We tried to cycle there on minor roads but ended up on the equivalent of the M1. We went to and from Annecy four times over the course of the weekend. Each time we rode on the hard shoulder of a motorway.

By Saturday evening I was much more myself. That was it. I was riding.

On the morning of the race we breakfasted at 5am then cycled down to Annecy for our 7am start. Here’s a shot I took of some of the 13,000 riders.

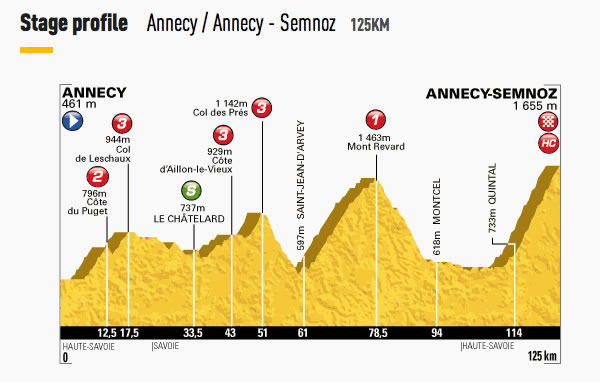

The ride was a mostly circular route that ended at the summit of Mont Semnoz, a very steep mountain and ski station that overlooked the town. It would also be the penultimate and potentially decisive stage of the Tour de France. Here’s a profile of the ride. It wasn’t especially long (81 miles) but fearfully hilly.

We planned to set off gently. I had no idea how I’d fare. That was true whether I’d been ill or not. This was unchartered territory.

Early on there were two ‘categorised’ climbs, hills that are steep enough to warrant a grade. They weren’t long or that steep which is why they were only ‘category 3’ and ‘category 2’. We had the ‘1’ and the ‘hors categorie’ (beyond categorisation) to come.

I felt a frisson of excitement riding a route (or ‘parcours’) the pros would be tackling two weeks later. Both early hills were pretty easy, especially at our moderate pace, and we reached the first food station hot but not too bothered.

Having completed a fair bit of climbing we were soon treated to some wondrous descents. The Etape is a ‘closed road’ event, meaning no cars, meaning you can use the full width of the road without the risk of being splattered to death.

After 60km we began the ascent of Mont Revard. This was a long climb, some 16km (10 miles). I hadn’t eaten for a while and had run out out of food. Foolishly I’d assumed there’d be a food station at the foot of the mountain. When you cycle long distances it’s important to keep your carbohydrate levels topped up. Failure to do so can result in what is known as ‘bonking’ or ‘hunger knock’. Symptoms include weakness, shaking, death and moaning.

“I need food, cuz,” I said to Luke. I couldn’t help noticing that Luke didn’t offer up any of his emergency cheese bagel.

I was flagging. My stomach felt totally empty. I reached hopelessly into my back pocket – only to find a tiny tube, like a miniature toothpaste, that I’d picked up at the first feed station. I’d even tried to hand it on to someone else since it looked so foul but now I bit the top off and squeezed some into my mouth.

An ill-tasting sugary paste it may have been, but it was enough. A small squirt every kilometre, washed down with liquid, kept me pedalling. To preserve my energy I rode in Luke’s slipstream and didn’t utter a word for 10km, at which point a fellow rider declared there was food 2km away.

“ABOUT FUCKING TIME!” I screeched, and rode on with renewed zest.

Once we reached the food stop I ate the weight of a medium-sized car and crammed the same into my pockets. The worst was to come but now that I knew I wouldn’t bonk all I felt was relief.

The descent of Mont Revard was fantastic, long sweeps combined with tight hairpins and stunning views. The descent of Muswell Hill takes 30 seconds. This went on for 20 minutes.

Once the road flattened out we knew what was to come: Mont Semnoz – 11km long at an average of 8.3%, the first and last three kilometres at over 10%.

By now the temperature was close to intolerable. I’ve never ridden in such heat. I certainly wouldn’t sunbathe in it. It was blistering, baking, broiling. At the food stations they were hosing down the riders.

What an unrelenting bastard Semnoz turned out to be. Chosen by the Tour organisers as the final climb of the Tour, today she was inflicting hurt on a bunch of wide-eyed amateurs.

A couple of kilometres in I saw a man lying motionless in the long grass with tubes up his nose, being tended to by doctors. Many were walking. Some had stopped and were leaning over their handlebars, seeking communion with God. Others toppled over due to the slow speed. The climb was exceptionally tough. I heard later an Englishman suffered a heart attack.

On the roadside there were signs telling us how many kilometres were left. 10, 9, 8, 7… Once we reached four I knew I’d be fine. The end was in sight.

As we approached the line, and with Luke to my left in red, an impromptu smile broke out across my funny face.

Here’s a celebration snap. The strain on my face clearly shows I have yet to invest in a carbon fibre frame.

And here’s Luke (his bike is lighter).

And that was it. We freewheeled back down to Annecy, ate a bowl of pasta, headed back along the M1 to our hotel, bagged up our bikes, consumed a dreadful meal at the hotel restaurant, exchanged war stories with our fellow riders, sunk a couple of cold ones and collapsed into bed, dreaming of fast descents and yellow jerseys.

*

Best present ever. Thanks Joan.

*

*

*

*

Luke had his bike stolen in transit. Bastards.

*

*

*

*